I am a Professor of Economics at Seattle University. I mainly study household behavior and demography in low- and middle-income countries, with forays into methods and criminal justice. Below are examples of some of my recently published research. More is available under the “Research” link.

Latest Research

Sub-Saharan Africa’s fertility levels are markedly higher than those of other regions. Using individual-level data, I show that the differences in fertility emerge among women with some primary education and narrow at higher levels. I argue that these patterns reflect lower school quality and higher child mortality in sub-Saharan Africa.

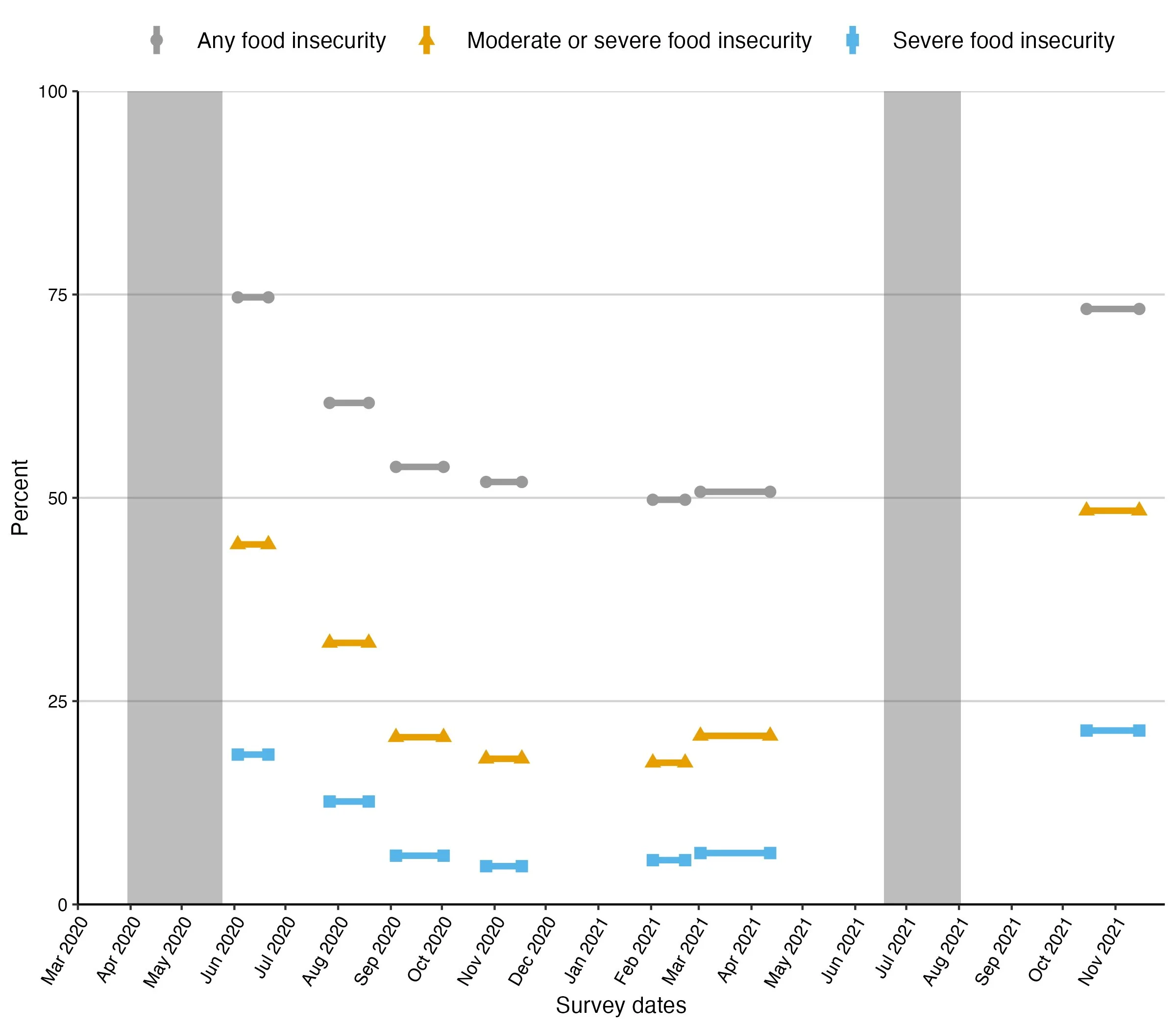

Uganda’s strict COVID-19 lockdowns led to substantial increases in household food insecurity both in the short and medium run. Using longitudinal data from high-frequency phone surveys, we show that coping mechanisms such as remittances and government assistance proved ineffective, and that many households shifted toward agriculture in response.